August 8, 2018

Paul Makdissi, Professor of Economics, University of Ottawa, Canada

Countries of the MENA rely mostly on consumption subsidies for reducing inequality. As we will illustrate below, a move from fuel subsidies towards food subsidies would be desirable. Unfortunately, some countries also started eliminating food subsidies. It is a bad timing for eliminating these food subsidies. As pointed out in IFPRI’s Global Food Policy Report 2018, the rise of anti-globalism may put pressure on the global food prices. In this post, I brainstorm about potential changes of these subsidies in four Arab countries.

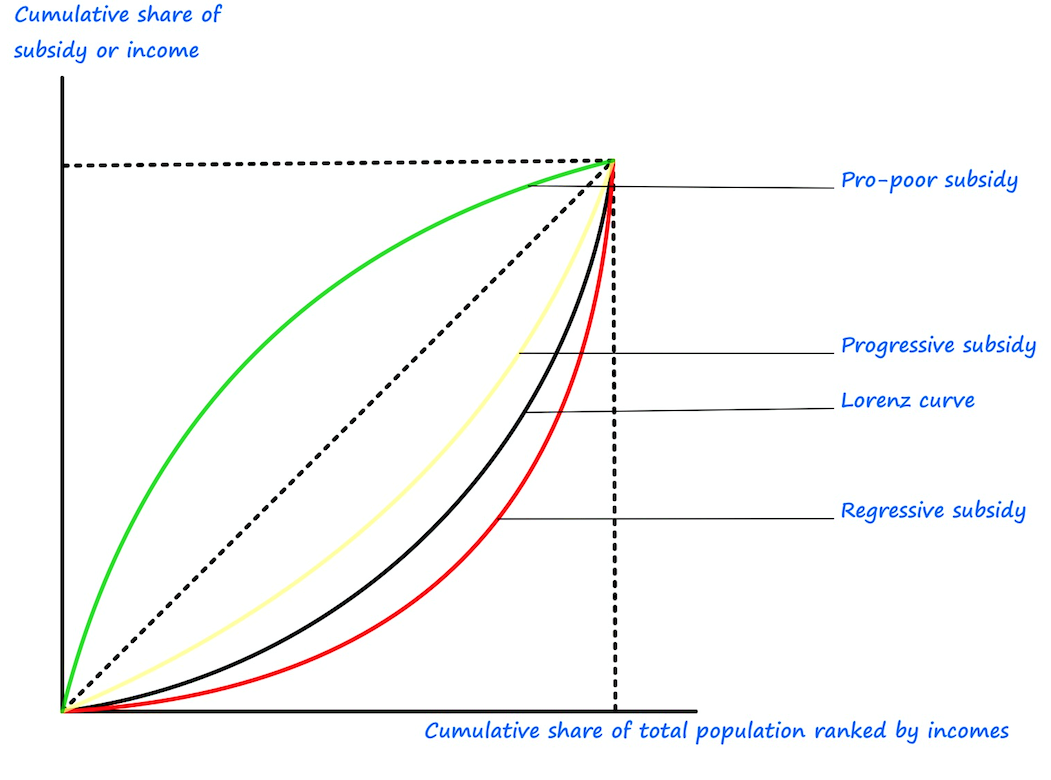

The redistributive performance of subsidies can be assessed by comparing the subsidies concentration curves to the Lorenz curve. Figure 1 depicts these two concepts. The Lorenz curve displays the cumulative share of total income earned by the x% poorest in the population. The concentration curve displays the cumulative proportion of a subsidy allocated to the x% poorest in the population. There are three cases:

- Regressive subsidy: the subsidy is more in favor of the rich than the distribution of income

- Pro-rich progressive subsidy: the subsidy is less in favor of the rich than the distribution of income

- Pro-poor progressive subsidy: the subsidy is more concentrated among the poor

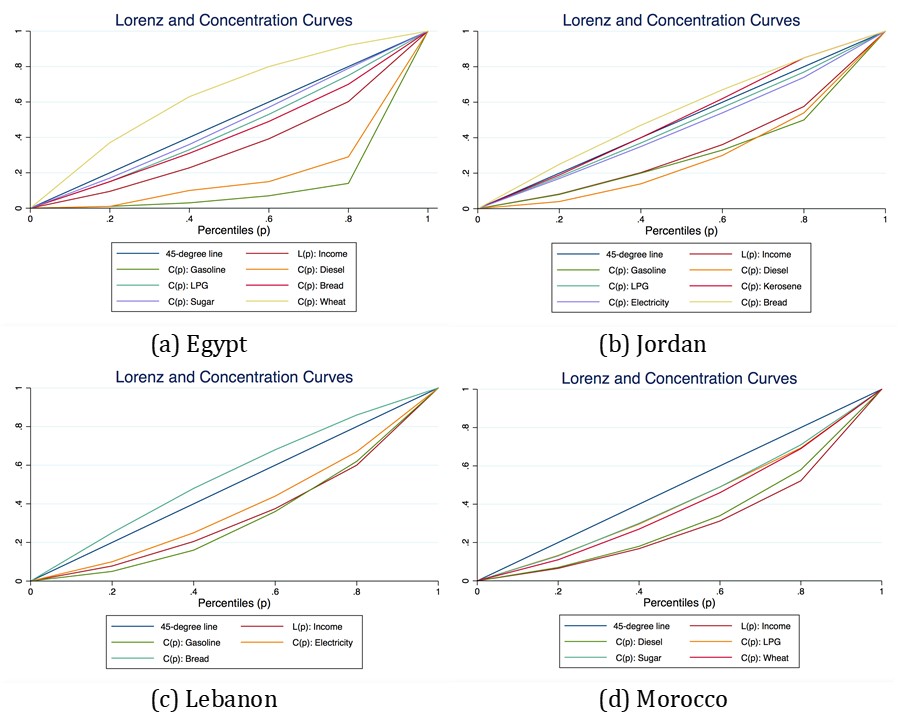

Source: My own calculation using quantile information from Sdralevich, et al. (2014) and from the World Bank Open Data.

Figure 2 displays the Lorenz and concentration curves of consumption subsidies for four Arab economies. In Egypt (2a), it is clear that subsidies on gasoline and diesel are highly regressive. Totally eliminating these subsidies would reduce inequality in Egypt. Since 2013, the Egyptian government is engaged in major reforms of consumption subsidies aiming at reducing these fuel subsidies. The subsidy on liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and all food subsidies are progressive. In addition, the subsidy on wheat is pro-poor. This would be an easy vehicle of compensation for the increase in fuel prices.

In Jordan (2b), the subsidies on gasoline and diesel are also regressive. All other subsidies are progressive and the subsidy on bread is pro-poor. The Jordanian government started reforming subsidies in 2012 by increasing prices on petroleum products. Last January, the government eliminated the subsidy on bread. This move increases inequality.

In Lebanon (2c), the subsidy on gasoline is regressive but the subsidy on electricity and on bread are both progressive. In addition, the subsidy on bread is pro-poor. At this date, no reform has been implemented.

In Morocco (2d), all subsidies are progressive. The government started decreasing subsidies in 2013. As of 2015, the only remaining subsidies in Morocco are the subsidies on liquefied petroleum gas, flour, and sugar.

Identifying potential subsidies reforms

The literature on marginal tax reforms indicates that concentration curves may be used to identify directions for marginal tax reforms (see Yitzhaki and Slemrod, 1991; Makdissi and Wodon, 2002; Duclos, Makdissi and Wodon, 2008). It is socially desirable to transfer funding from subsidies with lower concentration curves to the subsidies with higher concentration curves. One also needs to consider the efficiency cost of the reform i.e. what is the increase in the price of one good that compensates for the decrease in the price of the other good.

In an illustrative example, we use a method proposed by Duclos, Makdissi and Wodon (2008) to identify intervals for this efficiency cost. Duclos, Makdissi, and Araar (2014) compute this cost for an increase on fuel price used to finance a decrease of food price for Mexico. They find that this efficiency ratio is 1.04. This means that one should increase the price of fuel by 4% above the decrease of food price to have a budget-neutral balance. Let us use this 4% as example and brainstorm about the potential of savings if we decrease the most regressive fuel subsidy and use part of the proceeds to increase the most progressive food subsidy while increasing the wellbeing of the bottom 80% of the population.

Applying this methodology for Egypt yields to an interval of [0, 6.6] for the efficiency cost if one wants to decrease the subsidy on gasoline and increase the subsidy on wheat. If we assume that the real efficiency ratio is around 1.04, this means that 84.25% of the savings on the gasoline subsidy could be used to reduce the public deficit and 15.75% to increase the subsidy on wheat and this will still be welfare-improving for the bottom 80% of the population. Of course, one can do even better if a larger share of the savings is allocated on wheat subsidy or other food subsidies.

For Jordan, we perform the same thought experiment by decreasing the subsidy on diesel and increasing the subsidy on bread. In this case, 35% of the savings could be used to decrease the public deficit.

For Lebanon, we consider a decrease of the subsidy on gasoline and increase of the bread subsidy. In this case, 25.7% of the savings could be allocated to decrease the public deficit.

Finally, for Morocco, 13.3% of a decrease of the subsidy on diesel could be allocated to deficit reduction if the rest is allocated to increase the subsidy on sugar.

In conclusion, subsidy reforms have the potential of increasing welfare and decreasing poverty/ inequity in MENA countries. It is, therefore, pivotal that policy makers consider the redistribution impact of subsidy policies. The analysis presented in this blog shows that savings from reducing regressive fuel subsidies could be efficiently used to reduce public deficit and increase progressive food subsidies.